A New Year’s Day Concert

Sonata da Chiesa Op. 1 No. 1 Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713)

Salva nos from Op. 1 No. 1 Francesco Bonporti (1672-1749)

Toccata – Partite sopra l’aria della Folia Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725)

Sinfonia per Liuto Anon.

Largo-Allegro-Largo-Allegro

Sonata da Chiesa Op. 3 No. 5 Corelli

Intermission

Prelude- Allemande-Prelude Thomas Baltzar (1631?-1663)

Sinfonia-Recit -Aria, Largo-Recit-Ritornello & Aria-Recit-Aria, Andante-

Recit-Aria, Largo-Recit-Recit Accompagnato

Program Notes

Few composers have been as famous and influential in their own lifetimes as Arcangelo Corelli. His trio sonatas, solo sonatas and concerti grossi were the model for all composers who wrote in those Italianate forms. Indeed, Corelli may have been a little chauvinistic when it came to French music. Corelli was in charge of the orchestra which gave the debut of the young Handel’s oratorio La Resurezzione. Handel had composed a very French Overture, rather than an Italianate Sinfonia to introduce the piece. Corelli’s orchestra fell apart and could not get through this movement, and the Italian said to Handel ‘Ma, cara sassone, - But my dear Saxon, this is in the French style, which I do not understand.’ Handel went back to his desk and composed something more Italianate.

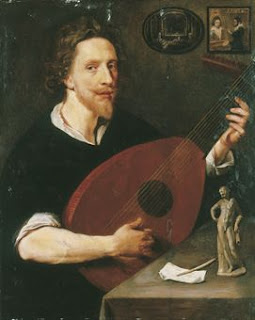

Corelli’s Opus 1 and 3 trio sonatas come with partbooks labeled ‘violino primo, violino secondo, organo’ and ‘violone o arcileuto’. The violone (what we would call a cello, but maybe a biggish one) and archlute book has melodic material shared with the violins, but also has the same figures above the notes as the organ part, which suggests that the archlute player, at least, did double duty as melodic bass and chordal instrument.

A contemporary description of the demeanor of Corelli, who is said to have dressed in all black, tells us that in performance ‘it was usual for his countenance to be distorted, his eyes to become as red as fire, and his eyeballs to roll as if in an agony’. Here then is a man with the diabolical image which Tartini’s ‘Devil’s Trill’ sonata alludes to and the Romantic violinist Paganini later exploited. Indeed, Stravinsky’s A Soldier’s Tale and 1970s country rock hit The Devil Went Down to Georgia also feature violin playing devils. Thomas Baltzar moved to England from his native Germany during the Commonwealth, that interregnum where there was no British court, and so, no courtly centre for music making. The composer John Wilson, previously musician-in-ordinary to Charles I and songwriter for Shakespeare plays, was making a living presenting public concerts in this period and the stupendous violinist Baltzar wowed Wilson's audience with the new-fangled German violin playing techniques. (English players had been rather stuck in a Renaissance rut, what with the fighting a civil war and everything.) John Wilson came out of the astounded audience came and checked Baltzar’s feet to make sure that he did not have devil’s hooves for feet ‘because he acted beyond the parts of a man’ with his virtuoso performance. The diarist John Evelyn says that on March 4th, 1656 ‘This night I was invited by Mr. Roger L'Estrange to heare the incomperable Lubicer (Baltzar was from Lübeck) on the Violin’.

That the manuscript that contains the anonymous Sinfonia for archlute and continuo comes from a manuscript which had been in the library of a Czech/Austrian dynasty of counts means it is probably Italian. Lutenists and theorbo players like Francesco Conti were employed at the Imperial court throughout the 18th century and Vivaldi, who died and is buried in Vienna, wrote some lute works in a texture that was being cultivated in German speaking lands. The Corelli-esque slow movements of this piece suggest the type of ornamentation that Estienne Roger published in Amsterdam claiming that they were Corelli’s own very florid ornaments.

Since so few High Baroque operas beyond a few of Handel’s are performed today Alessandro Scarlatti, who was a successful composer in that form, is perhaps less famous today than he might be. Similarly, his keyboard works are not as famous as those of his son Domenico though as you will hear, he was a spectacular composer for the harpsichord. The chord changes of his variations on La Folia will not be unfamiliar to regular Musicians In Ordinary concert-goers, who will have heard violin variations, guitar variations and even vulgar political songs performed to the stock bass line and tune which developed from a guitar ground of the early 17th century. (Listen for the ‘strum-strummmm-a-strum-strum’ rhythm.) Corelli has his own variations on the Folia for violin and continuo and Liszt and Rachmaninov (who erroneously calls it a ‘Theme of Corelli) wrote variations on it in the 19th and 20th century.

An early guitar alfabeto notation Folia shows how the strums go (down, down, up).

There's a bit more information in the one Philip will play.

Alessandro Scarlatti was also a very prolific composer of cantatas both with just continuo and with other instruments, again, a much under-performed genre considering what a large slice of so many composers’ works it comprises. Very often the Cantata’s text is a description of the joys or sorrows (usually the sorrows) of an amorous shepherd, in the kind of perfect love only possible in the pastoral tradition. The pains of this shepherd are usually reported by another shepherd looking on. This all sounds terribly mannered to us today, but the pastoral tradition was used for centuries to demonstrate how perfect political entities might work, how the perfect host might behave, and, in the case of song, how the perfect lover might feel. Is it any less mannered than a present day hospital drama or cop show?

Throughout the cantata we see Scarlatti deploy the bag of tricks used by a composer of operatic ‘music-drama’. He moves seamlessly between speech-like declamation and arioso passages in the recitatives as the emotions of the shepherd swirl. The arias, with their infectious melodies, narrow the focus onto one ‘affect’ of the spurned lover and in the sad airs, use suspensions in the violins to paint his anguish.

Happy New Year.

Christopher Verrette has been a member of the violin section of Tafelmusik since 1993 and is a frequent soloist and leader with the orchestra. He holds a Bachelor of Music and a Performer’s Certificate from Indiana University and contributed to the development of early music in the American Midwest as a founding member of the Chicago Baroque Ensemble and Ensemble Voltaire, and as a guest director with the Indianapolis Baroque Orchestra. He collaborates with many ensembles around North America, performing music from seven centuries on violin, viola, rebec, vielle and viola d’amore. He was concertmaster for a recording of rarely heard classical symphonies for an anthology soon to be released by Indiana University Press, and most recently collaborated with Sylvia Tyson on the companion recording to her novel, Joyner’s Dream.

Edwin Huizinga has toured throughout the world with Tafelmusik and performed with the Aradia Ensemble and I Furiosi. He has soloed with the Oberlin, Note Bene and San Francisco Baroque Orchestras, the San Bernardino Symphony, the Carmel Bach Festival Orchestra, the Sacramento Baroque Ensemble and the Kitchener-Waterloo Chamber Orchestra. He has been the concert master of the San Francisco Bach Chorale, the guest director of the Atlanta Baroque Orchestra, has toured with the Wallfisch Band under Gustav Leonhardt and was a guest artist at the Conservatory of Amsterdam. Currently a member of the ensemble Passemezzo Moderno, and recently made his Carnegie Hall debut with the Theatre of Early Music, he has a passion for bringing chamber music to the people and was a founding member of the Classical Revolution in San Francisco in 2006. Throughout 2012 he toured extensively with his band The Wooden Sky.

Philip Fournier is Titular Organist of the Toronto Oratory, Director of the Chant Schola & Oratory Children’s Choir. He specializes in Gregorian Chant, which he studied at Solesmes with Dom Saulnier. He gives solo organ recitals regularly at the Oratory, is guest organist of the Toronto Tallis Choir, artistic director and continuo player of the St. Vincent’s Baroque Soloists, and is active as a composer. His organ and harpsichord teachers have included James David Christie at the College of the Holy Cross, Russell Saunders, Paul O’Dette & Arthur Haas at the Eastman School of Music, and Robert Clark & John Metz at Arizona State. Mr. Fournier was the first Organ Scholar of the College of the Holy Cross, Worcester USA, and was subsequently named a Fenwick Scholar, the highest academic honour given by the College. He was one of the recitalists of the Chapel Artists Series there in 2011. He won the Historical Organ in America competition in 1992 and performed at Arizona State University on the Paul Fritts organ, and was awarded a recital on the Flentrop instrument at Duke University. Mr. Fournier was Organist & Director of Music at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Portland Maine, from 2000-2007, during which time he founded the Cathedral Schola Cantorum for the restoration of Gregorian Chant and Renaissance Polyphony to the Stational Masses of the Diocese of Portland.